Protecting planetary boundaries

Interview with Johan Rockström, director, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, and Virchow Prize Laureate 2024

Earth’s life-support systems are under increasing pressure, with seven of nine planetary boundaries already breached. Urgent transformations in energy, food and global cooperation are essential to prevent irreversible harm to the planet

What are planetary boundaries?

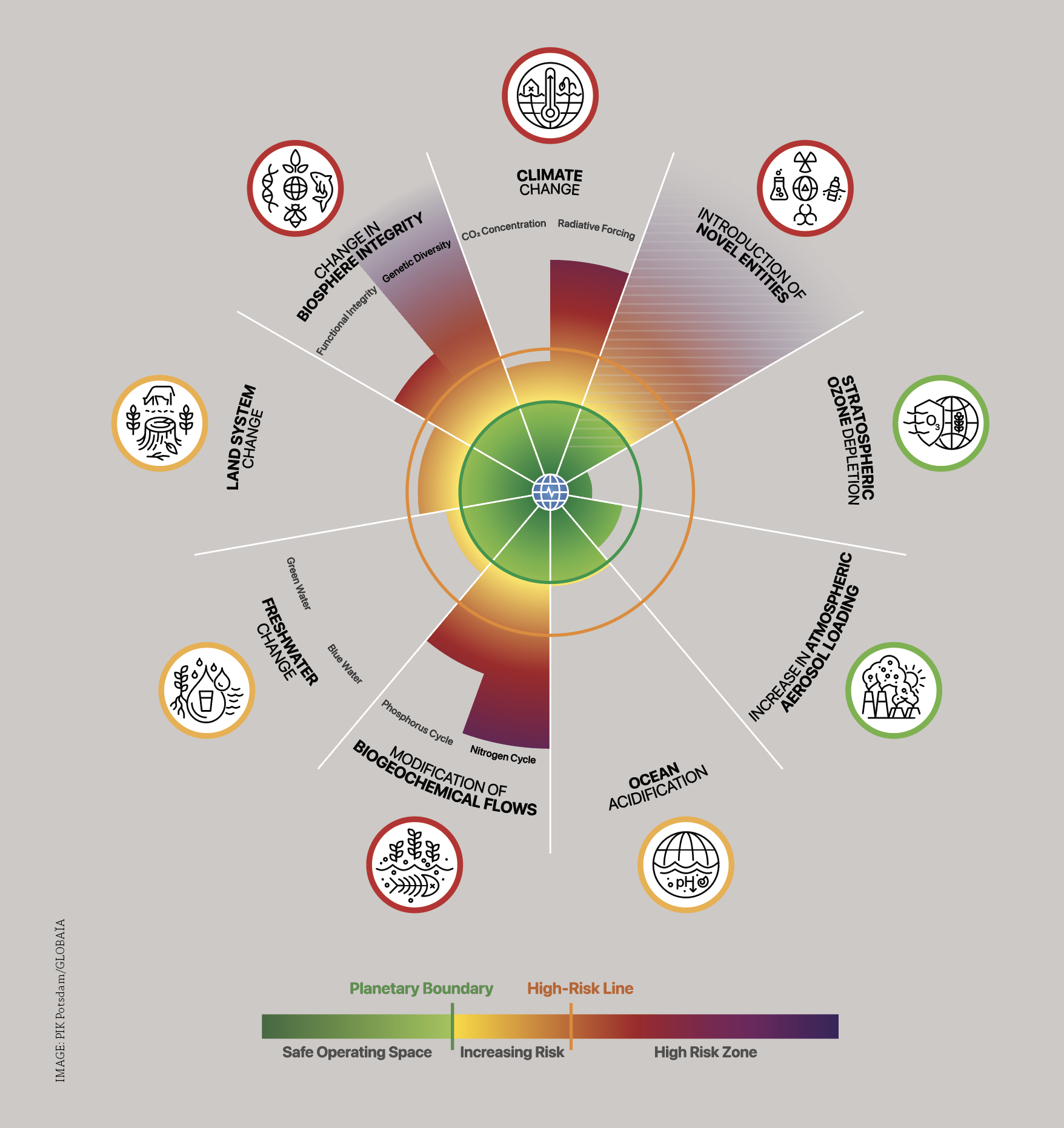

The planetary boundaries framework defines the safe operating space for humanity on Earth. Scientists have identified nine critical Earth-system processes (see Figure), each tracked by quantitative control variables, that together regulate the planet’s stability and resilience. As a risk-based assessment, the safe boundary is at the lower end of scientific uncertainty. Crossing a boundary moves us from a safe green area to enter the yellow danger zone of uncertainty, and if you reach the upper range with a high certainty of causing permanent damage, you enter the red high-risk zone. Crossing a boundary does not mean immediate collapse, but it raises the risk of large-scale, abrupt and potentially irreversible changes of the Earth system.

Put simply, humans have become a large force on our planet. We’re hitting the ceiling even on hardwired biophysical processes that regulate the functioning of the whole Earth system. Earth is a biogeophysical system where large processes interact and self-regulate; but pushed too far, these processes can cross biophysically defined thresholds and shift the Earth system beyond conditions that can support humanity.

Which boundaries may have already been crossed?

We are in a planetary crisis, with seven of the nine planetary boundaries already breached; on all these seven boundaries we are moving in the wrong direction. The climate change boundary is in the red zone with accelerating warming. We’re in the red on biodiversity loss and land configuration boundaries. We are cutting down big rainforests and boreal and temperate forests that are shifting from carbon sinks to carbon sources. Blue and green water variables are outside their safe space. Nitrogen and phosphorus are in the deep red, causing dead zones in oceans, eutrophication and destabilised ecosystems. We’re still unable to fully quantify the over 100,000 chemical compounds on the market, but scientific papers have concluded we’re overloading the Earth system with novel entities. The latest science shows that we have now also breached the ocean acidification boundary.

How are climate change and biodiversity loss harming human health?

We’ve transgressed the climate change boundary and warming is amplifying extreme heat, which affects humans’ capacity to cope with lethal heat waves and extreme impacts. Scientific evidence shows that if we approach 2°C of warming, life-threatening heat will affect up to 2 billion people in the tropical zone – and the International Court of Justice affirmed in its Advisory Opinion on the obligations of states in respect of climate change, that 1.5°C is the primary temperature limit to be held under the Paris Agreement. Heatwaves are already deadly: the 2003 heatwave in Europe caused the premature death of around 70,000 people.

On biodiversity and climate change, in the last 70 years, most of the pandemics and epidemics – including Covid-19, Ebola and SARS – have been viruses that crossed from animals to humans. The risk of these mutations increases with the unsustainable overexploitation of nature because of greater exposure between humans and nature and also the changing composition of wildlife species. More generalist species such as bats and rats reach higher densities and spread more quickly. Transgressing the biodiversity boundary will likely increase the risk of large pandemics.

The freshwater boundary, which covers both green and blue water, has been breached. This affects food security, undermining stable yields of staple crops and raising the risk of malnutrition, particularly among vulnerable communities in developing countries and poor communities. Ill health will more likely result from unhealthy food, in this case from a lack of food, linked to the transgressions of the biodiversity, climate change and freshwater boundaries.

What available solutions must be implemented now?

We need to become stewards of the entire planet, with leadership at the planetary scale. We need more collective action and more trust between countries, not less. The trend line is moving backwards towards a domestic, nationalistic, short-sighted focus, when we need more collective action to manage our global commons. The only way to keep the planet within its safe operating space is to recognise that the ocean, ice sheets, rainforests, peatlands and permafrost are the global commons we all depend on, and we have to manage them collectively.

Delivering on existing global agreements, including the Paris Agreement, is essential. Every boundary translates into a budget.

For the climate boundary, it’s 200 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide remaining to stay within a safe operating space. That means today we must reduce emissions by 10% annually.

Which transformations are most urgent?

Within these budgets, two transformations are required urgently: the energy transition and the food system transition. The food system is a dominant driver of overconsumption of freshwater, overuse of nitrogen and phosphorus, greenhouse gas emissions, land system change and biodiversity loss. We must move away from unsustainable, unhealthy, planet-damaging agricultural systems into regenerative, sustainable and healthy food systems. This is fully possible. We know how to produce food in ways to return within planetary boundaries.

Moreover, unhealthy food is one of the biggest global health issues. Between 10 and 11 million people die every year because of malnutrition, over-nutrition and non-communicable diseases related to unhealthy food. Moving towards healthy diets, which we can define scientifically, gives us win-win outcomes because planetary health and human health are closely interdependent.

What role do policy and economic incentives play in driving these transformations?

We can accelerate these solutions for both the energy and food system transitions. All the solutions exist. Technologically it’s straightforward: solar, wind, biomass, hydro, fuel cells, conservation tillage, circular nutrient fluxes, reduce biodiversity loss. It requires economic incentives – policy that discourages planet-damaging and planetary-boundary threatening actions and incentivises sustainable, healthy, within-planetary-boundary operating activities. It needs to be easy for citizens to make the right choices. That combination of the energy and food system transitions and smart economic policies is at the heart of planetary stewardship. Indeed, with the ICJ’s recent ruling on climate change, countries now have a clear duty to address the planetary crisis and can be held accountable.