Health politics: forever changed

The impact of COVID-19 on health politics is a landscape that will never look the same as the world pursues – with greater determination – the highest attainable standard of health for every human being

Political choices have always played a key role in shaping health – no matter in what kind of political system. The message of the United Nations and the Sustainable Development Goals is that all governments should choose health and enable their citizens and the people living within their borders access to the best possible health and well-being. This goal is also expressed in the constitution of the World Health Organization: “The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.” This statement by the founders of the WHO has needed to be repeatedly reinforced – it is far from being realised. Indeed, following the impact of COVID-19, development gains in health and poverty alleviation have been rolled back and concerns over human rights abuses in relation to the pandemic have arisen.

Already before COVID-19, the health and human rights debate and the debate on the social determinants of health continuously drew attention to persisting health inequalities. What determines a person’s health can rarely be influenced by individuals alone – it is shaped by the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. Those conditions include structural factors such as socio-economic status, education, neighbourhood and physical environment, employment and social support networks, as well as access to health care. These in turn are influenced by political decisions, as the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health has highlighted: these decisions shape the distribution of money, power and resources not only among people but also among countries and regions of the world.

Ten years after the commission, a new, more radical health debate has emerged. It questions whether enough has been done to address structural inequalities but also whether a totally new approach based on ‘critical justice’ is required to truly address the root causes. Gender, for example, was not named in the WHO constitution as a key determinant of health, and the true extent of structural racism as experienced today was not understood. And although processes of globalisation have pulled many people out of poverty, they have also contributed to new dependencies and new inequalities.

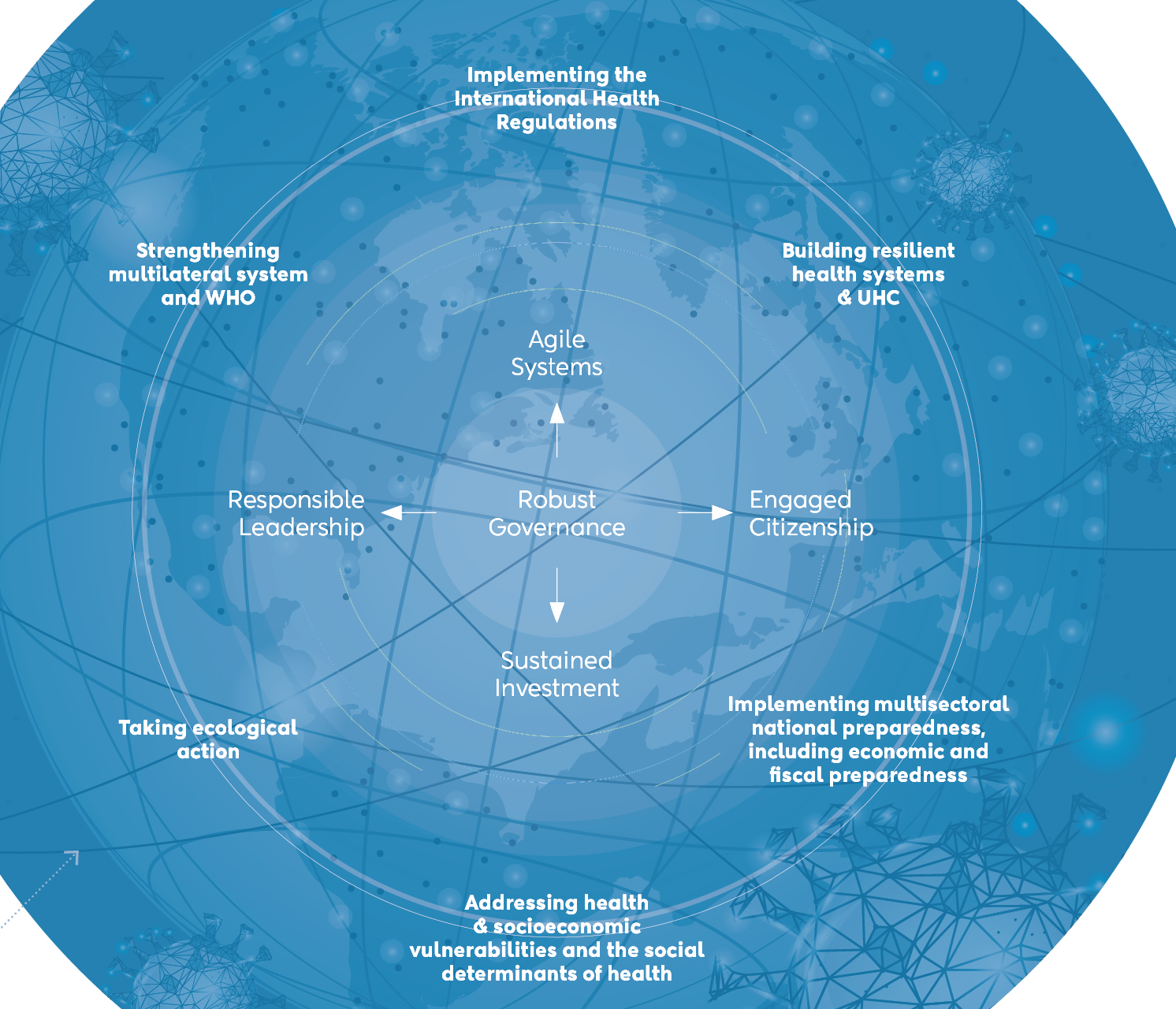

The need to address the determinants of health therefore ranges from the very local to global decision-making based on a ‘Health in All Policies’ approach. With the SDGs the UN has attempted to provide a road map for a more equitable future and to set the key theme: leave no one behind. It calls on sectors, countries and organisations to work together to create a sustainable future. But the first assessments at the end of 2019 already gave cause for concern – in health, the world was falling behind. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has since made that gap even larger. More people are falling into poverty, food security is threatened and many other priority health issues do not get the attention they deserve.

Dimensions of health

If anything, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of all three dimensions of the WHO definition of health: the physical, the mental and the social. People might escape the virus but be subjected to mental health problems, domestic violence or unemployment. The virus has also underscored the fact that the vulnerable fall ill and die in higher numbers. It has demonstrated with great clarity that there can be no health security without social security. As countries debate how they can build back better, they must address these key issues to avoid driving their societies apart. That means they must build into an uncertain future.

The discussion on social determinants in the context of COVID-19 has made clear how politicised an issue health has become, and how significant political choices are. Health, in the past, was considered an issue that would bring people and countries together – who could possibly be opposed to creating more and better health? Today, health is divisive – groups of citizens no longer trust their government, do not trust science and set themselves against others, for example by refusing to wear a mask. Some states no longer want to work together to fight the virus; others want to make sure that their citizens have access to a potential vaccine first. Strange political bedfellows have emerged – some populists join forces with anti-vaccine groups; other populists fight to have access to a vaccine as rapidly as possible through what has been termed “vaccine nationalism”.

The world was not ready for the virus – despite many warnings. But the virus could also not have hit the world at a more difficult time. Geopolitical shifts in combination with the rise of populist leaders have led to a weakening of multilateralism. One major country has announced it will leave the World Health Organization – the key global agency for countries to work together on health. The fiscal space in many countries has shrunk again, just when it was starting to pick up support for strengthening universal health coverage, as outlined in our 2019 edition in this series, Health: A Political Choice – Delivering Universal Health Coverage 2030. Funding for the United Nations and its agencies is no longer assured. New initiatives such as COVAX to ensure a common goods approach to vaccine development for COVID-19 have received strong support from more than 170 countries but are still not endorsed by some of the most powerful ones.

The ‘long tail’ of COVID-19 will involve dealing not only with the long-term health effects of the virus but also with the consequences of a divided world and of increasingly divided societies. The Global Preparedness Monitoring Board has titled its new report A World in Disorder. It underlines that as a world we have the knowledge, the resources and the technologies to deal with such a threat, and yet it seems we are failing.

That underlines the message so many contributions in this book put forward: a rethink of health policies to include the determinants of health at all levels is required not only for success, but also for trust. Determined political leadership at national and global levels is in high demand. Otherwise the political fallout of the COVID-19 crisis could be much longer-lasting and devastating than the direct health impact of the virus.